Southern History Comes Alive on Daufuskie Island

The storied past of Daufuskie Island reads like a Southern history textbook come to life – and if you’ve never heard of this fascinating place, you’re about to get a crash course in one of America’s most culturally rich hidden gems.

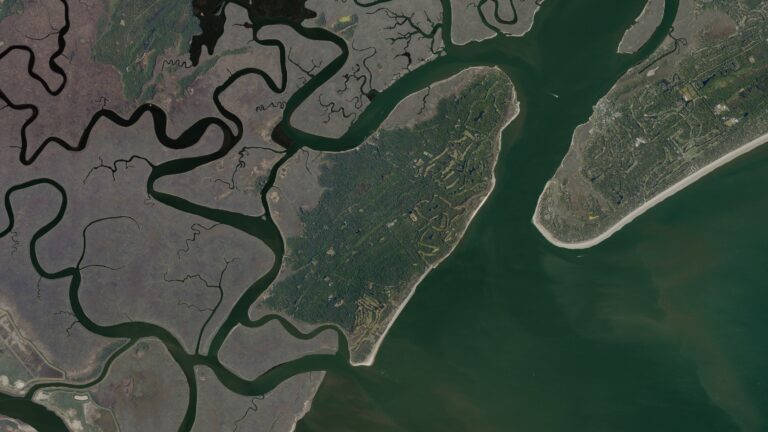

Sitting pretty between Savannah, Georgia and Hilton Head, South Carolina, this remote barrier island has seen it all – from indigenous settlements to European colonization, slavery, war, and the incredible preservation of Gullah culture. And with only 400 residents and zero bridges connecting it to the mainland, Daufuskie remains deliciously untouched by the modern world.

The Complete (and Completely Fascinating) History of Daufuskie Island

Native Americans: The OG Daufuskie Residents

If you’re wondering about that unique name, “Daufuskie” actually means “Sharp Feather” in the language of its original inhabitants. Cool, right?

Long before Europeans showed up with their flags and diseases, Native Americans were living their best island lives on Daufuskie for literally thousands of years. Archaeological evidence shows human activity going back at least 10,000 years – with shell middens and artifacts telling the story of these original islanders.

The Cusabo people (aka “people of the river”) built impressive stuff here – log lodges, massive canoes, and even walled villages. Later, the Muskogean nations and Yamacraw Indians thrived by hunting and fishing the abundant waters surrounding the island.

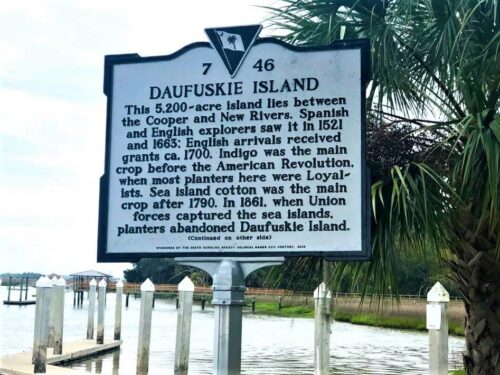

Everything changed when the Europeans arrived in the early 1500s. Spain called dibs first in 1521, claiming Daufuskie as part of their territory stretching from St. Augustine to Charleston. But the French weren’t far behind, eyeing nearby Port Royal just four years later.

European Drama: Colonies, Conflicts, and Cotton

By the mid-1600s, English explorers like Captain William Hilton were sniffing around the Lowcountry, paving the way for serious colonization drama.

In 1684, things got spicy when Spanish soldiers recruited native warriors to fight against Scottish settlers in Port Royal – just the first chapter in the messy story of Europeans dragging Native Americans into their colonial beef.

Then came the real bloodshed between 1715-1717 with the Yamasee Uprising. Three brutal battles were fought on Daufuskie’s southwestern shore – an area now cheerfully called “Bloody Point”. Not ominous at all!

The English land-grab started officially in 1707 when Thomas Cowte received the first English land grant. By 1737, King George II was handing out Daufuskie real estate to Captain David Mongin for fighting Spanish pirates. European families fleeing religious persecution, like the Mongins and Martinangelos, settled here and quickly became plantation bigwigs.

While all this colonial warfare was happening, the Spanish left some lasting contributions to the island:

- “Tabby” construction – a unique building technique using oyster shells

- “Marsh tackys” – special horses bred to navigate the sticky pluff mud

The late 1700s transformed Daufuskie into a serious agricultural powerhouse. While early planters grew indigo, rice, and live oak for shipbuilding, the real star of the show was sea island cotton. This variety became world-famous for its superior qualities – longer, finer, and stronger than any other cotton on the market.

By the time of the American Revolution, at least eleven plantations were operating on tiny Daufuskie Island. And speaking of the Revolution, the island earned the nickname “Little Bermuda” because its residents were such British loyalists. Despite backing the losing team, Daufuskie made it through the Revolutionary War relatively unscathed.

Slavery, Civil War, and Cultural Resilience

Let’s be real – the prosperity of Daufuskie’s plantations was built entirely on human suffering.

Large numbers of enslaved West Africans were forcibly brought to the island to work cotton and rice fields. Through this tremendous hardship, these resilient people established what would become known as Gullah culture – a unique blend of African traditions, European influences, and Lowcountry adaptations.

When the Civil War erupted, seven working plantations operated on Daufuskie. But the war changed everything. Union forces quickly occupied the Beaufort-area islands, including Daufuskie, using the island to support their siege of Fort Pulaski. About 1,600 Union troops moved in, causing white plantation owners and their enslaved people to flee.

The Gullah Legacy: Culture That Refused to Die

Here’s where Daufuskie’s story gets really interesting – the isolation that preserved a culture.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, formerly enslaved people returned to the island to work in oyster canneries and logging. Because Daufuskie was so remote and accessible only by water, Gullah culture flourished here in ways impossible in more connected places.

The Gullah people created a tight-knit community that actually crossed racial lines – pretty much unheard of in the post-Civil War South. Their dialect evolved into a distinctive form of English heavily influenced by West African languages. Today, descendants of these enslaved Africans maintain cultural traditions through language, food, music, and spiritual practices that directly reflect their African heritage.

The 20th century wasn’t kind to this unique community. Pollution closed the oyster beds in the 1950s, tanking the island’s economy. By the 1980s, the Gullah population had plummeted from over 2,000 to approximately 60 people. Around the same time, developers started creating fancy residential communities with names like Bloody Point, Melrose, and Haig Point.

Luckily, preservation efforts stepped in just in time. The entire island was designated a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982, recognizing its Gullah and Civil War history. The district includes 18 historic properties and 56 contributing sites, with folk housing dating from 1890-1930.

Today, Daufuskie Island remains a living museum of Southern history. Its tabby ruins, historic structures, and community traditions tell the stories of indigenous peoples, European colonizers, enslaved Africans, and cultural survival.

The island’s inaccessibility – requiring ferry or barge transportation with no bridge or airport – has ironically become its greatest asset, protecting both its environment and its irreplaceable cultural heritage for future generations. Sometimes the hardest places to reach hold the best stories.